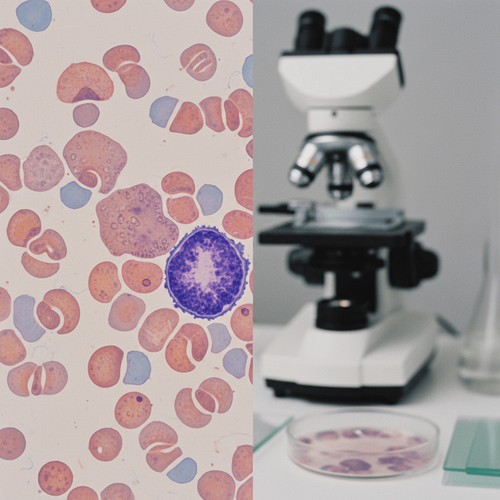

The question of when to start enteral nutrition in patients with septic shock remains a thorny one. Guidelines offer broad recommendations, but the devil is always in the details at the bedside. Is the gut adequately perfused? Can it tolerate the metabolic demands of feeding? This isn't a theoretical exercise; getting it wrong can have dire consequences, from worsening septic shock to intestinal ischemia.

A recent commentary tackles this very practical problem, moving beyond blanket recommendations to a framework for individualizing feeding decisions. It emphasizes the importance of continuous assessment of gut perfusion, arguing that the gut itself provides the best signals for tolerance. For the intensivist juggling multiple organ systems, this approach offers a crucial layer of nuance in a high-stakes clinical setting.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotMoving beyond standardized protocols, the focus shifts to individualized assessment of gut perfusion as the primary guide for initiating enteral nutrition.

- The DataWhile hard data is limited, clinical signs like abdominal distension, high gastric residual volumes, and worsening lactate are critical indicators of gut intolerance.

- The ActionImplement a protocol for serial abdominal exams and gastric residual volume monitoring, and be prepared to hold or reduce feeds based on these real-time assessments.

Assessing the Gut at the Bedside

The cornerstone of this individualized approach is a thorough and repeated assessment of gut perfusion. This goes beyond simply checking for bowel sounds. Clinicians should be vigilant for signs of abdominal distension, tenderness, or changes in bowel habits. Monitoring gastric residual volumes (GRVs) is also key; persistently high GRVs can indicate delayed gastric emptying and potential intolerance to enteral nutrition.

Furthermore, keep a close eye on hemodynamic parameters. A sudden drop in blood pressure or an increase in vasopressor requirements during feeding may signal mesenteric ischemia. Serial lactate measurements can also be informative, with rising lactate levels potentially indicating inadequate gut perfusion. Consider also the trend of base excess, as a worsening metabolic acidosis can precede frank bowel necrosis.

Red Flags for Withholding Feeds

When should you hold or reduce enteral feeds? Any of the following should raise serious concerns: new onset or worsening abdominal distension, persistent vomiting, high gastric residual volumes (typically >500 mL), signs of peritonitis, rising lactate levels, or increasing vasopressor requirements during feeding. If any of these red flags are present, immediately stop the feeds and reassess the patient's hemodynamic status.

The 2016 ESPEN guidelines for nutrition in critical care recommend early enteral nutrition within 24-48 hours of ICU admission, but these recommendations are largely based on studies that exclude patients with severe shock or gut ischemia. These guidelines do not account for the nuances of individual gut perfusion, which is the central argument of the featured commentary. Therefore, a rigid adherence to these guidelines can be dangerous and inappropriate.

Limitations of the Evidence

It's vital to acknowledge the limitations of the evidence base. There is a paucity of large, randomized controlled trials specifically addressing the optimal timing of enteral nutrition in septic shock patients with varying degrees of gut dysfunction. Most studies are observational or retrospective, making it difficult to establish causality. Furthermore, the definition of "gut dysfunction" itself is often subjective and inconsistent across studies.

Another key limitation is the heterogeneity of the patient population. Septic shock encompasses a wide spectrum of underlying infections, comorbidities, and pre-existing nutritional states, all of which can influence the response to enteral feeding. Any recommendations must be interpreted in the context of the individual patient's clinical picture.

Economic Considerations

While the focus is often on clinical outcomes, economic factors also play a role. The cost of parenteral nutrition (PN) is significantly higher than enteral nutrition. Prolonged use of PN not only increases hospital costs but also raises the risk of complications such as catheter-related bloodstream infections. Thus, there is a financial incentive to transition patients to enteral feeding as soon as it is safely feasible.

Moreover, the implementation of a protocol for close monitoring of gut perfusion requires dedicated nursing time and resources. Frequent abdominal exams, GRV measurements, and lactate monitoring all add to the workload of already stretched ICU staff. Hospitals must ensure adequate staffing levels to support this individualized approach.

Implementing this bedside assessment protocol requires a shift in mindset. It means empowering nurses to recognize early signs of gut intolerance and to communicate these concerns to the medical team promptly. It also requires a collaborative approach, with physicians, nurses, and dietitians working together to tailor feeding strategies to the individual patient's needs. This may necessitate more frequent adjustments to feeding rates and formulas, demanding a higher level of vigilance and communication.

From a billing perspective, ensure accurate documentation of the rationale for withholding or adjusting enteral feeds. This documentation should clearly outline the clinical findings that support the decision-making process, particularly in cases where early enteral nutrition is delayed beyond the standard guidelines. Such documentation is essential for justifying medical necessity to payers.

LSF-2624223347 | January 2026

How to cite this article

MacReady R. Gut perfusion dictates enteral nutrition timing in sepsis. The Life Science Feed. Published January 1, 2026. Updated January 1, 2026. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Singer, P., Blaser, A. R., Berger, M. M., Alhazzani, W., Calder, P. C., Casaer, M. P., ... & Bischoff, S. C. (2019). ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clinical Nutrition, 38(1), 48-79.

- McClave, S. A., Taylor, B. E., Martindale, R. G., Warren, M. M., Johnson, D. R., Braunschweig, C., ... & Ayers, P. (2016). Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 40(2), 159-211.

- Reintam Blaser, A., Starkopf, J., Alhazzani, W., Berger, M. M., Casaer, M. P., De Waele, J., ... & Singer, P. (2017). Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: ESICM clinical practice guidelines. Intensive Care Medicine, 43(3), 380-398.