Unexplained hypoglycemia in a patient receiving therapy for colorectal cancer should prompt targeted evaluation beyond nutritional intake or infection. Insulin autoimmune syndrome (IAS) is a rare, often drug-induced cause in which autoantibodies bind endogenous insulin, creating a reservoir that unpredictably releases insulin and precipitates symptomatic glucose drops. For busy oncology teams, missing this diagnosis risks repeated emergency visits, treatment interruptions, and avoidable harm.

Practical, coordinated steps can stabilize patients while preserving anticancer intent. A focused laboratory workup that includes plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and insulin autoantibodies, a careful medication review to identify potential triggers, and early collaboration between oncology, endocrinology, pharmacy, and nursing provide a path to safe de-escalation of risk and a plan for ongoing cancer care.

Insulin autoimmune syndrome in oncology practice: recognition, confirmation, and coordinated care

In oncology, recurrent hypoglycemia is uncommon and easily attributed to poor oral intake, infection, adrenal insufficiency, or diabetes therapies. Yet a subset of patients develop insulin autoimmune syndrome (IAS), an immune-mediated condition where antibodies bind circulating insulin, sequester it, and later release it, causing delayed or unpredictable hypoglycemia. IAS can be triggered by medications used in or around colorectal cancer care. Recognizing this pattern early prevents a cascade of unnecessary imaging and invasive testing, avoids mislabeling the patient as malingering or nonadherent, and supports uninterrupted cancer treatment with appropriate modifications.

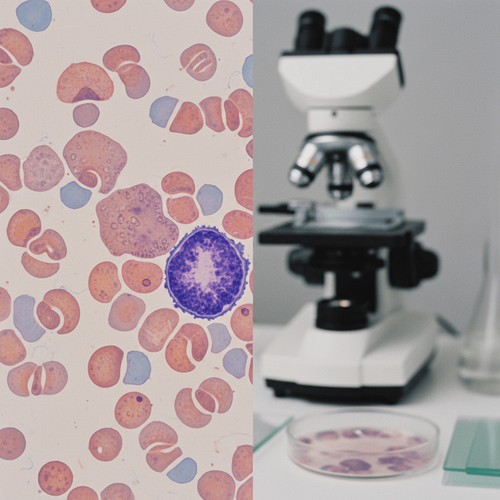

IAS typically presents with neuroglycopenic symptoms that fluctuate with meals and time of day. The mechanistic hallmark is the presence of insulin autoantibodies leading to high measured insulin levels, relatively high or inappropriately normal C-peptide, and hypoglycemia without exogenous insulin exposure. Because antibody-bound insulin can interfere with immunoassays, clinicians should interpret results in clinical context and consider free versus total insulin assays when available. The most immediate priorities are patient safety, identification and cessation of the provoking medication when feasible, and symptom control to avoid emergency department visits and treatment delays.

When to suspect IAS in colorectal cancer care

Think IAS when an oncology patient without access to insulin develops recurrent hypoglycemia with discordant laboratory values or with variable timing that is not explained by fasting alone. Consider these clue patterns:

- Hypoglycemia that occurs several hours after meals rather than strictly in the fasting state, reflecting delayed insulin release from antibody complexes.

- Markedly elevated total insulin levels during hypoglycemia, with C-peptide that is not suppressed, suggesting endogenous insulin exposure.

- Episodes that improve transiently with dextrose but recur as insulin is released from antibody reservoirs, sometimes described as rebound hypoglycemia.

- No history of insulin or sulfonylurea use; a negative sulfonylurea/meglitinide screen when available supports the diagnosis.

- Onset after initiation of a new anticancer or supportive medication, with partial resolution after the drug is held.

In colorectal cancer care, multiple factors may converge: polypharmacy, changes in hepatic metabolism, immune activation, and the use of agents that can modulate immune tolerance or act as haptens. While triggers vary, the practical point is to systematically screen the medication list, including anticancer regimens, premedications, antiemetics, analgesics, antibiotics, supplements, and over-the-counter agents.

Maintain a broad differential diagnosis during initial assessment to avoid anchoring:

- Medication-induced hypoglycemia (insulin, sulfonylureas, meglitinides): check medication access, pill counts when appropriate, and a sulfonylurea/meglitinide screen.

- Insulinoma: fasting hypoglycemia with high insulin and C-peptide, negative insulin autoantibodies, and symptomatic relief during supervised fast when glucose is maintained.

- Adrenal insufficiency: consider if hypotension, hyponatremia, or cancer therapy-associated adrenal axis suppression; obtain morning cortisol and ACTH as indicated.

- Non-islet cell tumor hypoglycemia: often with low insulin and C-peptide, driven by IGF-2 or big IGF-2 from large tumors or liver involvement.

- Sepsis or hepatic dysfunction: impaired gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis.

- Post-gastrectomy hypoglycemia (if prior surgery): rapid gastric emptying with exaggerated incretin response.

Features tipping the balance toward IAS include onset after medication changes, paradoxically high insulin concentrations that do not match clinical severity, and postprandial or late-postprandial symptom clusters. Family and nursing observations that hypoglycemia follows carbohydrate-heavy snacks can be particularly telling.

Confirming IAS: laboratory workup and common pitfalls

The most efficient way to confirm IAS is to capture a critical blood sample at the time of symptoms. If point-of-care glucose is low, collect venous blood promptly before administering dextrose, whenever feasible and safe. The initial panel should include:

- Plasma glucose during symptoms.

- Insulin and C-peptide levels obtained concurrently.

- Insulin autoantibodies.

- Beta-hydroxybutyrate (often suppressed in hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia).

- Sulfonylurea/meglitinide screen when available.

Optional tests can be tailored to clinical suspicion: morning cortisol and ACTH if adrenal insufficiency is a concern; liver panel if hepatic dysfunction is suspected; thyroid function if broader autoimmunity is being considered. Imaging to localize insulinoma should not be pursued until biochemical data support that path.

Interpretation essentials:

- Insulin high or inappropriately normal with hypoglycemia and C-peptide not suppressed suggests endogenous insulin exposure. Positive insulin autoantibodies support IAS.

- Assay interference is common. Antibody-bound insulin can artificially elevate total insulin or, depending on the assay, yield misleading values. If clinical and laboratory findings diverge, discuss with the laboratory about free versus total insulin assays, heterophile antibody blocking, or alternative platforms.

- Do not rely on a 72-hour fast to exclude IAS. Many patients have postprandial hypoglycemia; prolonged fasting may not precipitate events and is burdensome for oncology patients.

- Timing matters: Late postprandial samples may be more revealing than fasting specimens in IAS due to delayed insulin release.

Documentation that closes the loop includes clear charting of Whipple triad during at least one episode: symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, low measured plasma glucose, and symptom resolution with glucose correction. Positive insulin autoantibodies in that context strongly favor IAS. Once IAS is confirmed or highly likely, shift quickly to pragmatic management while completing any remaining tests.

Management and prevention: medication review, stabilization, and care coordination

Stabilization and prevention of recurrence rest on three pillars: removing the trigger, blunting glycemic swings, and coordinating oncologic care to maintain cancer control.

1) Identify and stop the culprit medication if feasible

- Perform a line-by-line review of recent medication changes, including anticancer agents, premedications, antiemetics, antibiotics, analgesics, and supplements. Evaluate both timing and biologic plausibility.

- Consult pharmacy for immunogenicity or hapten potential and known associations with insulin autoantibodies.

- Discuss oncology-intent alternatives. Many regimens have feasible substitutions or dose-scheduling adjustments that preserve efficacy while reducing risk of recurrent hypoglycemia.

- Document the adverse drug reaction in the chart and allergy list, and file appropriate pharmacovigilance reports.

2) Immediate safety and symptom control

- Provide a hypoglycemia rescue plan: oral glucose tablets or gel for alert patients; if NPO or severely symptomatic, IV dextrose with monitored rebound risk.

- Education at bedside: recognize symptoms, confirm with meter when possible, treat promptly, and follow rescue carbohydrates with a snack that includes protein and complex carbohydrate to reduce rebound.

- Consider continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) to detect asymptomatic episodes, especially during chemotherapy cycles or steroid tapers. CGM trend arrows help patients and nurses anticipate nadirs.

- Arrange driving and fall-risk precautions until episodes abate. Issue a written plan for caregivers.

3) Blunt postprandial insulin surges and antibody-driven release

- Nutritional strategy: small, frequent meals; limit simple sugars; emphasize low-glycemic index carbohydrates; include protein and fat with meals to slow absorption; consider a bedtime slow-release carbohydrate (e.g., cornstarch) for nocturnal dips.

- Pharmacologic adjuncts under endocrine guidance: acarbose to attenuate postprandial glucose peaks; diazoxide may reduce insulin secretion in some cases; glucocorticoids can dampen antibody production and reduce hypoglycemia in moderate to severe presentations.

- Escalation for refractory, severe cases: therapeutic plasma exchange to lower antibody burden; B-cell directed therapy has been used in select life-threatening, refractory cases. These steps warrant multidisciplinary risk-benefit review given concurrent cancer therapy.

4) Coordinate oncology therapy without compromising outcomes

- Synchronize medication changes with oncology cycles to minimize treatment gaps; use bridging strategies where appropriate.

- Set a monitoring cadence: daily checks in the acute phase, then spacing to pre-infusion and 24 to 72 hours post-infusion when patterns are predictable.

- Communicate the plan across infusion nurses, inpatient teams, and primary care to prevent duplicate triggers or conflicting instructions.

5) Define success and duration of management

- Clinical targets: absence of symptomatic hypoglycemia, no emergency visits, and a return to routine oncology therapy with manageable monitoring.

- Laboratory targets: falling insulin autoantibody titers over time can be reassuring but are not required for discharge from intensive monitoring if the patient remains asymptomatic.

- De-escalate nutritional and pharmacologic adjuncts gradually to avoid rebound; taper steroids when used, with attention to potential steroid-related hyperglycemia and infection risk in oncology patients.

6) Practical documentation and handoff

- Create an IAS-specific problem list entry that includes the suspected trigger, diagnostic criteria met, and the management plan.

- Embed an order set for future symptomatic episodes: critical labs to draw before dextrose, rescue options, and notification triggers to endocrinology/oncology.

- Provide the patient with a concise wallet card noting IAS, the trigger medication, and emergency steps.

Clinical pearls and pitfalls

- Do not rule out IAS because a supervised fast is negative. Many cases are postprandial; capture late-postprandial labs.

- Interpret insulin values with caution. If the clinical picture and autoantibody status suggest IAS, discuss assay interference with the laboratory.

- Beware of rebound after IV dextrose. Plan a follow-up snack or infusion adjustment to blunt subsequent drops.

- Revisit the medication list at every cycle. New supportive care drugs can retrigger hypoglycemia even after initial stabilization.

- Engage the patient. Symptom logs aligned with meal content often reveal patterns that guide intervention.

Suggested workflow for oncology clinics

- At first episode: verify plasma glucose; obtain insulin, C-peptide, insulin autoantibodies, beta-hydroxybutyrate, and sulfonylurea screen if available before dextrose, when safe.

- Same day: pharmacy-led medication trigger screen; nursing education on rescue protocol; brief nutrition consult with low-glycemic plan.

- Within 48 hours: endocrinology huddle to interpret labs; provisional IAS diagnosis if autoantibodies positive and biochemistry concordant.

- By next cycle: implement anticancer regimen adjustment if a trigger is identified; arrange CGM for two weeks to map risk windows.

- Follow-up: weekly check-ins until asymptomatic; taper adjuncts thoughtfully; consider repeat autoantibody titer for documentation.

For patients and caregivers, a clear, empathetic explanation builds trust: the immune system has made antibodies to insulin, which can trap and then release it unpredictably, lowering sugar without warning. The focus is to remove the trigger when possible, smooth out meal-related swings, provide quick rescue tools, and keep cancer care on track. This framing reassures patients that there is a plan and that the care team is coordinating across disciplines.

Finally, close the loop on learning. Add IAS to internal adverse event dashboards. Share de-identified case learning points with infusion and inpatient teams. If the provoking agent is reintroduced for oncologic necessity, set a preemptive monitoring plan and informed consent conversation that covers the risk of recurrence and the contingency plan for prompt intervention.

LSF-6241134508 | November 2025

How to cite this article

Sato B. Insulin autoimmune syndrome in oncology: recognition and care. The Life Science Feed. Published November 28, 2025. Updated November 28, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- A case report of insulin autoimmune syndrome induced by drugs for colorectal cancer. PubMed. Accessed November 28, 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41239648/