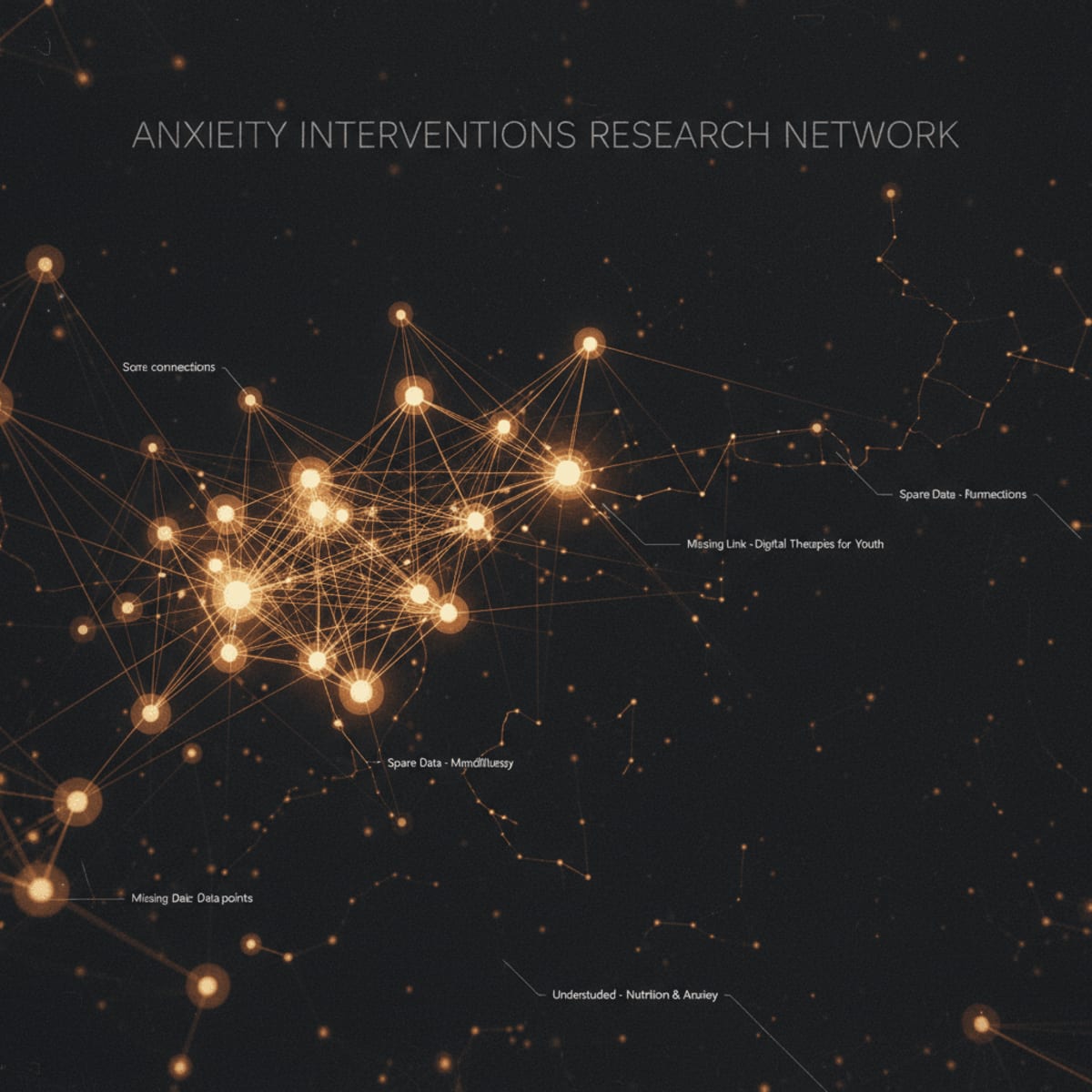

Anxiety disorders are ubiquitous, yet the arsenal of evidence-based psychosocial interventions feels… incomplete. A recent "evidence map and guideline appraisal" underscores this sentiment. It highlights not just what we know about treating anxiety disorders in adults, but, more importantly, where the significant gaps lie. This isn't merely an academic exercise; it's a call to strategically direct future research efforts for maximum clinical impact.

The implications extend beyond the consulting room. How do these findings shape our understanding of resource allocation, treatment accessibility, and the ongoing refinement of clinical guidelines for anxiety management? Let's dissect the key takeaways and pinpoint the areas demanding immediate attention.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotCurrent anxiety treatment guidelines may overemphasize certain interventions while neglecting others due to incomplete evidence.

- The DataEvidence maps reveal specific under-researched areas, such as interventions for specific anxiety subtypes (e.g., social anxiety with comorbid conditions) or the long-term effectiveness of combined therapies.

- The ActionClinicians should critically evaluate the evidence base for their chosen interventions and consider participating in research or advocating for studies addressing identified gaps.

Guideline Alignment and Divergence

Where do current anxiety disorder guidelines stand in light of this evidence mapping? Many guidelines, such as those from the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), heavily promote Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and exposure therapy as first-line treatments. This isn't necessarily wrong, but it may reflect a publication bias or an over-reliance on studies focusing on these specific modalities. Are we shortchanging patients by not rigorously exploring other potentially effective interventions, particularly for those who don't respond to traditional CBT? The guidelines need to be living documents, constantly updated to reflect a broader, more nuanced understanding of the treatment psychosocial interventions.

Identifying the Research Voids

The real value of an evidence map lies in pinpointing what we don't know. What are the specific populations or intervention types that are under-researched? For instance, how effective are mindfulness-based interventions for older adults with generalized anxiety disorders and comorbid medical conditions? What about the long-term outcomes of combining pharmacological and psychosocial approaches in patients with severe panic disorder? These are the questions that should be driving future research grants and clinical trial designs.

We also need more research into the implementation and dissemination of evidence-based practices in diverse settings. What works in a university clinic may not be feasible or effective in a rural community health center. Understanding these contextual factors is essential for bridging the gap between research and real-world practice. The research should emphasize the need for culturally adapted interventions, especially among marginalized populations who may face unique stressors and barriers to mental health care.

Methodological Caveats

Let's be blunt: not all research is created equal. Many studies in the field of mental health suffer from methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, lack of randomization, or reliance on self-report measures. These limitations can significantly impact the validity and generalizability of the findings. We need to demand more rigorous research designs, including larger, multi-center trials with objective outcome measures. Is anyone tracking biomarkers alongside subjective reports? Probably not enough.

Furthermore, the field needs to address the issue of publication bias, where studies with positive results are more likely to be published than those with negative or null findings. This can create a distorted picture of the true effectiveness of different interventions. The only way to counter this is through greater transparency and the widespread adoption of pre-registration for clinical trials.

The Economic Angle

Anxiety disorders are not just a clinical problem; they're an economic one. The cost of untreated anxiety, in terms of lost productivity, healthcare utilization, and social welfare, is staggering. Yet, access to evidence-based psychosocial interventions is often limited by financial barriers and insurance coverage. How do we make these treatments more affordable and accessible to those who need them most? Telehealth and group therapy models may offer cost-effective alternatives to traditional one-on-one therapy, but they need to be rigorously evaluated for their effectiveness and scalability.

The economic equation also extends to research funding. Who is paying for these studies, and what are their vested interests? Are pharmaceutical companies disproportionately funding research on pharmacological treatments, while neglecting psychosocial interventions? We need to ensure that research funding is allocated fairly and transparently, based on the needs of patients and the priorities of the healthcare system, not just the bottom line of corporations.

Clinicians need to be proactive in advocating for better access to evidence-based psychosocial interventions for their patients with anxiety disorders. This may involve lobbying insurance companies to expand coverage, working with hospitals to develop more affordable treatment programs, or participating in research to generate new evidence.

Consider the administrative burden. Documenting the necessity of specific therapies for reimbursement can be time-consuming, requiring clinicians to navigate complex billing codes and prior authorization processes. Streamlining these processes and advocating for policies that reduce administrative barriers are critical steps toward improving access to care.

LSF-3058589209 | January 2026

How to cite this article

El-Sayed H. Gaps in evidence for psychosocial anxiety interventions. The Life Science Feed. Published January 26, 2026. Updated January 26, 2026. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Bandelow, B., Michaelis, S., & Wedekind, D. (2017). Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 19(2), 93–107.

- Craske, M. G., Stein, M. B., Eley, T. C., Milad, M. R., Holmes, A., & Rapee, R. M. (2017). Anxiety disorders. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 3(1), 1-20.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2011). Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management. NICE guideline CG113.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.