The specter of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) looms large over nearly every aspect of modern medicine. While much attention is paid to systemic infections, a recent study from the United Kingdom highlights a concerning trend: the shifting landscape of Staphylococcus aureus resistance in atopic dermatitis. This isn't just a regional problem; it's a bellwether signaling the potential erosion of our topical antimicrobial armamentarium globally.

The question isn't simply if resistance will emerge, but how clinicians adapt when first-line agents falter. What selective pressures are at play? Is this a mupirocin problem, a fusidic acid problem, or a broader consequence of widespread antimicrobial use? We need to consider if current prescribing habits are accelerating the inevitable, and what proactive strategies can mitigate the risk.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotAntimicrobial resistance in atopic dermatitis isn't a static problem; ongoing surveillance is essential to adapt treatment strategies.

- The DataThe study showed a regional increase in resistance to commonly used topical antibiotics, suggesting localized prescribing practices influence resistance patterns.

- The ActionClinicians should incorporate local antibiogram data into their prescribing decisions for topical antibiotics in atopic dermatitis.

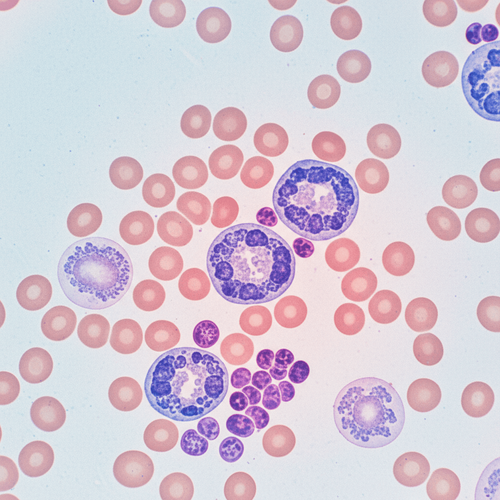

The treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) frequently involves topical antimicrobials to combat Staphylococcus aureus colonization, a known exacerbating factor. However, the increasing prevalence of S. aureus strains resistant to commonly prescribed topical antibiotics poses a significant clinical challenge. We must ask: are we adequately tracking this shift, and are current prescribing practices sustainable?

Understanding the Selective Pressures

The development of antimicrobial resistance isn't random; it's a direct consequence of selective pressure. Every time an antibiotic is used, susceptible bacteria are eliminated, leaving resistant strains to thrive. In the context of AD, frequent or prolonged use of topical mupirocin or fusidic acid creates an environment ripe for resistance to emerge. Are patients being educated thoroughly on appropriate application techniques and duration of use? Are clinicians reflexively prescribing these agents without considering alternative strategies, like topical corticosteroids or non-antibiotic antiseptics?

The Mupirocin and Fusidic Acid Conundrum

Mupirocin and fusidic acid have long been mainstays in the treatment of S. aureus-associated skin infections, including those complicating AD. However, their widespread use has led to a predictable rise in resistance. Some strains of S. aureus now harbor genes that confer resistance to both agents, limiting therapeutic options. The question is: should these agents be reserved for more severe cases or for situations where other treatments have failed? A tiered approach, guided by local resistance patterns, may be a more prudent strategy.

Further complicating matters is the potential for cross-resistance. Resistance to one antimicrobial can sometimes lead to resistance to others, even if they belong to different classes. This phenomenon, driven by shared resistance mechanisms, underscores the importance of judicious antimicrobial use and comprehensive AMR surveillance. If we continue down this path, it's not just mupirocin and fusidic acid we risk losing, but potentially entire classes of antimicrobials.

Beyond Traditional Antibiotics

The looming threat of widespread resistance necessitates exploring alternative strategies for managing S. aureus colonization in AD. These may include topical antiseptics like chlorhexidine or hypochlorous acid, which have a broader spectrum of activity and a lower propensity for inducing resistance. Probiotics, both topical and oral, are also being investigated for their potential to modulate the skin microbiome and reduce S. aureus colonization. While these alternatives show promise, rigorous clinical trials are needed to establish their efficacy and safety.

Another avenue worth exploring is targeted antimicrobial therapy based on individual patient characteristics and the specific S. aureus strain involved. This approach requires rapid and accurate diagnostic testing to identify resistance genes and guide treatment decisions. While such testing may be more expensive upfront, it could ultimately reduce the overall burden of AMR by ensuring that antimicrobials are used only when truly necessary.

The Economic Burden of Resistance

The rise of antimicrobial resistance carries a significant economic burden. Infections caused by resistant bacteria are more difficult and expensive to treat, often requiring prolonged hospital stays and more potent, costly medications. In the context of AD, resistance to topical antimicrobials can lead to more frequent and severe flares, resulting in increased healthcare utilization and reduced quality of life. Who ultimately bears this cost? The patients, the healthcare system, and society as a whole. A proactive approach to antimicrobial stewardship is not just a matter of clinical responsibility; it's an economic imperative.

A Call for Proactive Stewardship

The changing landscape of S. aureus resistance in AD demands a paradigm shift in how clinicians approach treatment. We need to move away from routine, empiric antimicrobial use and embrace a more targeted, stewardship-focused approach. This includes educating patients on appropriate antimicrobial use, utilizing diagnostic testing to guide treatment decisions, and exploring alternative strategies for managing S. aureus colonization. The future of AD treatment depends on our ability to adapt and innovate in the face of evolving antimicrobial resistance.

The increasing resistance to common topical antibiotics will require clinicians to spend more time counseling patients on proper hygiene and emollient use, potentially impacting clinic workflow. The need for bacterial cultures to guide antibiotic selection will increase laboratory costs and may require pre-authorization from insurers. Furthermore, treatment failures due to resistant organisms may lead to increased use of systemic antibiotics, with their attendant risks and side effects, further driving up costs and patient burden.

LSF-3337324381 | December 2025

How to cite this article

Webb M. Antimicrobial resistance creep in atopic dermatitis what comes next?. The Life Science Feed. Published December 7, 2025. Updated December 7, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- David, M. Z., & Daum, R. S. (2010). Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 23(3), 616-687.

- রেজিস্টার্ড, എ., et al. (2023). Changing Staphylococcus aureus Resistance in Atopic Dermatitis: Implications for Topical Antimicrobial Use From a Regional Study in the United Kingdom. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 143(11), 2118-2126.e4.

- Leung, D. Y. M., Boguniewicz, M., Howell, M. D., Nomura, I., & Hamid, Q. A. (2004). New insights into atopic dermatitis. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 113(5), 651-657.