Early-onset Alzheimer's disease (EOAD), defined by symptom onset before age 65, presents unique diagnostic and management challenges. While genetic mutations like presenilin-1 (PSEN1) are known causes, the sporadic form of EOAD is more common. A recent study highlighted differences in comorbidity profiles between these two groups, raising the question of whether our screening strategies should be tailored accordingly. Should a diagnosis of EOAD automatically trigger a specific panel of comorbidity screenings? It's a question of optimizing patient care and resource allocation.

This analysis focuses on how these findings impact clinical practice, specifically in terms of proactive comorbidity screening. The goal is not just to identify these conditions but to manage them effectively, potentially improving the overall quality of life for individuals with EOAD. We'll examine the data and consider practical steps clinicians can take.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The Pivot Comorbidity profiles differ between sporadic and PSEN1-mutation related EOAD, suggesting a need to refine screening approaches.

- The DataNeuropathological changes, not just age of onset, significantly influence comorbidity risk in Alzheimer's dementia.

- The ActionImplement a tiered screening protocol that considers both genetic status and detailed neuropathological assessments in EOAD patients.

Background

The distinction between sporadic and genetic forms of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is more than academic; it impacts patient management. While PSEN1 mutations are a well-defined cause of EOAD, the majority of EOAD cases arise sporadically. This means we need to understand the underlying mechanisms driving comorbidity development in each group. Are there shared pathways, or do different etiological factors lead to distinct patterns?

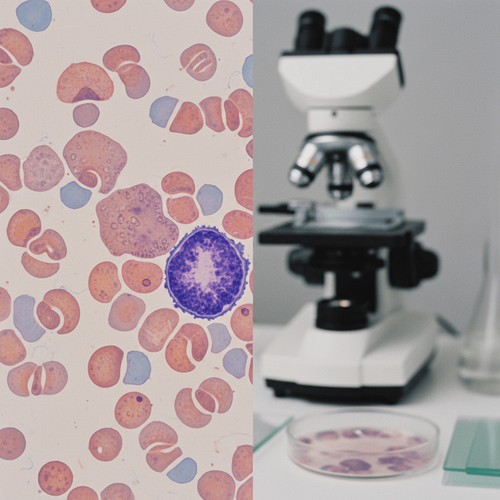

This study highlights the importance of considering neuropathological changes alongside genetic status. For instance, the presence of Lewy body pathology or cerebrovascular disease can significantly alter the comorbidity profile. This argues against a one-size-fits-all approach to screening.

Guideline Comparison

Current guidelines, such as those from the Alzheimer's Association and the National Institute on Aging, focus primarily on the diagnosis and management of cognitive symptoms. They offer limited guidance on specific comorbidity screening protocols for EOAD. This study's findings suggest that such guidelines may need to be expanded to include recommendations for tailored screening based on both genetic and neuropathological factors. For example, the NICE guidelines on dementia (NG97) emphasize holistic assessment but do not provide specific algorithms for comorbidity screening based on AD subtype. This research offers a potential framework for refining those assessments.

Study Limitations

The biggest issue here is sample size. Any study looking at relatively rare genetic subtypes of Alzheimer's faces an uphill battle to recruit enough participants. Small sample sizes inherently limit the statistical power and generalizability of findings. We need to consider whether the observed differences in comorbidity profiles are truly representative of the broader EOAD population, or simply a reflection of random variation within a small cohort.

Furthermore, most studies, including this one, rely on retrospective data. This introduces the possibility of selection bias and incomplete information. A prospective study, while more challenging to conduct, would provide more robust evidence.

Practical Screening Adjustments

Given these findings, what concrete changes can we make to our screening protocols? First, a detailed family history remains critical. While sporadic EOAD is more common, identifying potential genetic links can guide further investigation. Second, consider incorporating biomarkers that reflect underlying neuropathology. For example, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis for amyloid and tau proteins can provide valuable insights into the disease process. Third, be vigilant for non-cognitive symptoms, such as sleep disturbances or autonomic dysfunction, which may indicate specific comorbidities. For instance, REM sleep behavior disorder is strongly associated with Lewy body pathology. The Fourth, ensure all dementia patients have regular monitoring for depression and anxiety. Dementia diagnosis can increase the risk and mental state should be monitored at least yearly.

The implementation of tailored screening protocols will likely increase the initial diagnostic costs. More extensive genetic testing, CSF analysis, and advanced imaging studies will require investment. However, early detection and management of comorbidities can potentially reduce long-term healthcare costs by preventing complications and hospitalizations.

Workflow changes are also necessary. Neurologists will need to collaborate closely with geriatricians, psychiatrists, and other specialists to provide comprehensive care. This requires effective communication and coordination, which may be challenging in fragmented healthcare systems.

Reimbursement for comprehensive comorbidity screening in EOAD may be a barrier. Payers often focus on acute care rather than preventive measures. Advocacy efforts are needed to demonstrate the long-term value of proactive screening and ensure appropriate reimbursement policies are in place.

LSF-3357559285 | December 2025

How to cite this article

El-Sayed H. Early-onset alzheimer's dementia and comorbidities what to screen for?. The Life Science Feed. Published January 25, 2026. Updated January 25, 2026. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Alzheimer's Association. (2023). 2023 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 19(4), 1598-1695.

- National Institute on Aging. (2017). Alzheimer's Disease Genetics Fact Sheet. Retrieved from [https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-and-dementia/alzheimers-disease-genetics-fact-sheet](https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-and-dementia/alzheimers-disease-genetics-fact-sheet)

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. NICE guideline NG97.

- Jack, C. R., Jr, Bennett, D. A., Blennow, K., Carrillo, M. C., Dunn, B., Haeberlein, S. B., ... & Thies, B. (2018). NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 14(4), 535-562.