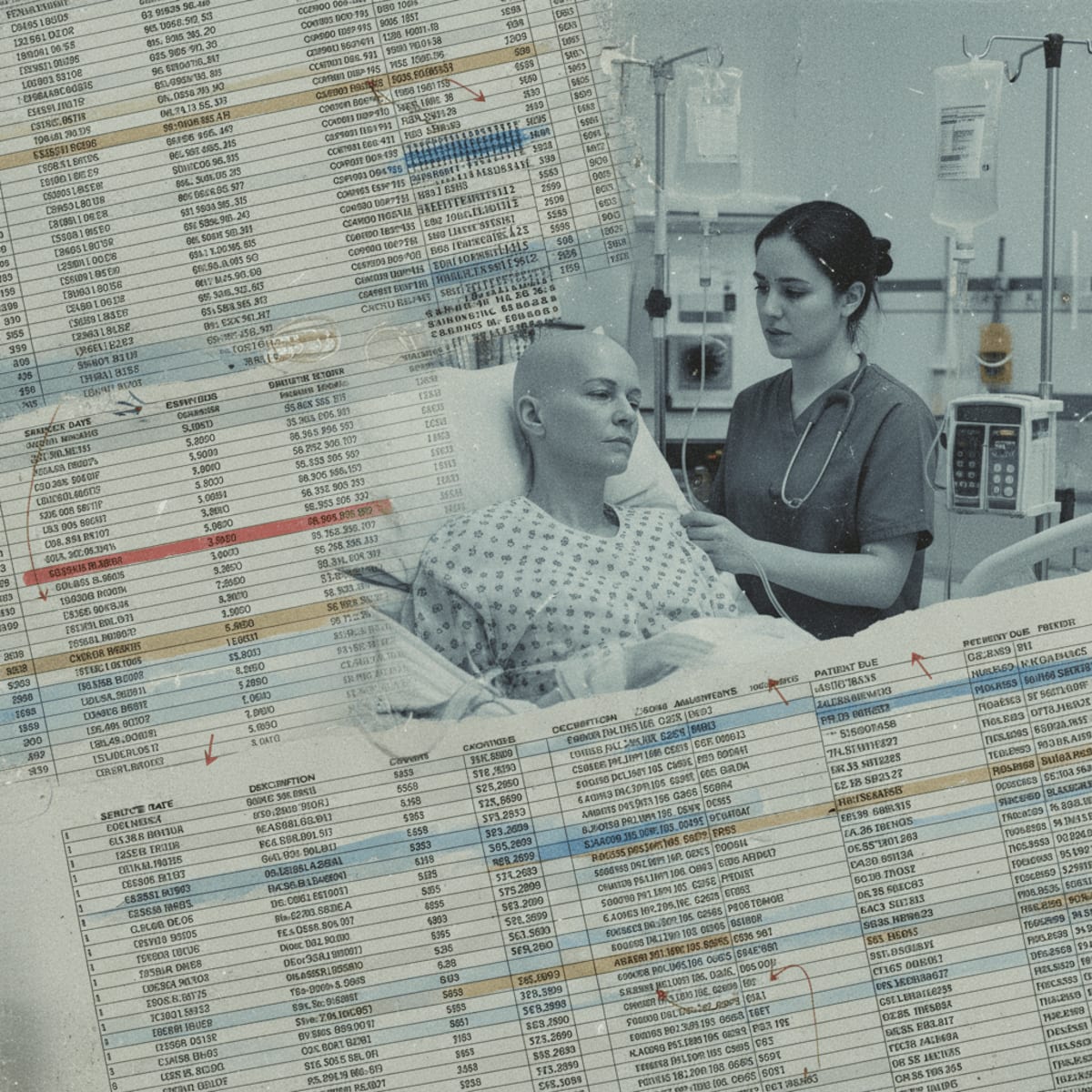

The chasm between recommended palliative care and its actual delivery to vulnerable cancer patients is not a matter of individual negligence, but a systemic failure. Referral-based models, while seemingly logical, often strand high-risk opioid users in a maze of bureaucratic hurdles and uncoordinated treatments. We need to examine the financial incentives that reward fragmentation and the regulatory barriers that prevent integrated, patient-centered care. How can we expect clinicians to prioritize holistic care when the system incentivizes volume over value?

The real question isn't whether palliative care is beneficial- the data is clear- but rather, who bears the cost of providing it? Until we address the fundamental economic disincentives, patients will continue to suffer needlessly. Oncologists and hospital administrators need to recognize that true reform demands a hard look at the bottom line and a willingness to challenge entrenched interests.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotCurrent referral-based palliative care models for oncology patients with opioid use disorder are failing, demanding a shift towards integrated, proactive care.

- The DataPatients in siloed care often experience poorer pain management and increased hospital readmissions.

- The ActionHealth systems should explore value-based reimbursement models that reward comprehensive, coordinated palliative care for high-risk patients.

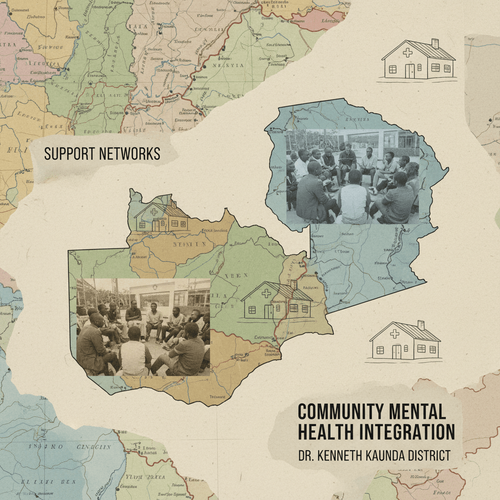

Guideline Mismatch

Major oncology guidelines, such as those from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), unequivocally recommend early integration of palliative care for all patients with advanced cancer, irrespective of prognosis. These guidelines stress the importance of addressing not only physical symptoms, but also psychological, social, and spiritual needs. However, the persistent reliance on siloed, referral-based systems directly contradicts these recommendations. How can we reconcile the stated commitment to patient-centered care with the practical reality of fragmented, inefficient service delivery?

The NCCN guidelines emphasize proactive assessment and management of pain, depression, and other common symptoms experienced by cancer patients. Yet, in many institutions, palliative care is only considered after a patient's condition has significantly deteriorated and multiple referrals have been made. This reactive approach fails to capitalize on the potential benefits of early intervention, such as improved quality of life and reduced healthcare costs. The financial structures in place actively disincentivize early intervention and holistic patient care.

The Referral Trap

Referral-based systems create a complex web of handoffs, often leading to delays in care and a lack of continuity. For oncology patients with a history of opioid abuse, this fragmented approach can be particularly detrimental. These patients may face stigma from healthcare providers, leading to reluctance in prescribing adequate pain relief. The lack of coordination between oncology, pain management, and addiction specialists can result in suboptimal symptom control and increased risk of adverse events. The question arises- how much does this systemic failure cost in terms of patient well-being and dollars spent treating avoidable consequences?

Moreover, the administrative burden associated with referrals can be substantial, requiring patients to navigate complex paperwork and scheduling processes. This burden is particularly onerous for individuals already struggling with the physical and emotional challenges of cancer. Streamlining the referral process and integrating palliative care services directly into oncology clinics could significantly improve access to timely and coordinated care.

Cost vs. Care

The prevailing fee-for-service reimbursement model incentivizes volume over value, rewarding providers for performing more procedures and tests, rather than for delivering comprehensive, patient-centered care. This creates a disincentive for investing in palliative care services, which may not generate the same level of revenue as other oncology treatments. The perverse incentives must be addressed.

Value-based care models, which reward providers for achieving specific outcomes and reducing costs, offer a promising alternative. By bundling payments for oncology and palliative care services, health systems can incentivize greater coordination and integration. This approach can also encourage providers to focus on preventive care and early intervention, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare expenditures. But will it actually be cheaper? Or just differently expensive? Consider the cost of staffing requirements and training.

Study Limitations

While the case for reforming siloed palliative care is compelling, any analysis must acknowledge inherent limitations. Retrospective studies, for example, are subject to selection bias and may not accurately reflect the experiences of all patients. Small sample sizes can limit the statistical power of findings, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. And of course, funding sources can influence the interpretation and dissemination of results. Clinicians must critically evaluate the available evidence and consider the specific context of their own institutions when making decisions about palliative care delivery.

Furthermore, the lack of standardized metrics for measuring the quality and effectiveness of palliative care makes it challenging to compare different models of care. Developing and implementing standardized outcome measures would facilitate more rigorous evaluation and continuous quality improvement. Let's see some better data before we upend the system completely.

The financial implications of reforming palliative care are significant. Hospitals may need to invest in additional staffing, such as palliative care physicians, nurses, and social workers. They may also need to implement new electronic health record systems to facilitate better communication and coordination among providers. However, these investments can be offset by reduced hospital readmissions, shorter lengths of stay, and improved patient satisfaction, which can improve hospital reputation and attract more patients. It all boils down to return on investment.

Moreover, changes in reimbursement models may require hospitals to renegotiate contracts with payers. This can be a complex and time-consuming process, but it is essential to ensure that hospitals are adequately compensated for providing comprehensive palliative care services. Palliative care is frequently under-billed, and this contributes to the perception that it is a money-losing operation.

LSF-8048687762 | December 2025

How to cite this article

Sato B. Reforming oncologic palliative care: who pays?. The Life Science Feed. Published December 26, 2025. Updated December 26, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Ferris, F. D., Bruera, E., Cherny, N., Dudgeon, D., Emanuel, L. L., & Fallon, M. (2009). Palliative cancer care: A synthesis of the evidence. *Annals of Internal Medicine, 151*(4), 244-258.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2023). *NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care*. Plymouth Meeting, PA: Author.

- Smith, T. J., Temin, S., Alesi, E. R., Abernethy, A. P., Balboni, T. A., Basch, E., ... & বৃত্ত, L. (2012). American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. *Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30*(8), 880-887.